SMS Quick Takes: Hazard Identification

Part 2 of Our Safety Risk Management (SRM) Series Under Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Part 5

In Part 1 of this series, we broke down systems and operating environments, the essential first step in SRM under 14 CFR part 5. With that context in place, you’re ready for the next phase: hazard identification.

Hazard identification is where SRM starts to take shape: it is the point where your understanding of how a system functions and the conditions in which it operates becomes a structured way to identify conditions that could reduce the margin of safety.

For many aircraft operators, designers, and manufacturers, this is one of the most challenging SRM steps to perform consistently. This post explains what a hazard is, how to recognize it, and how to describe it in a way that supports meaningful risk assessment and safety decision‑making.

✈️ What Is a Hazard?

For SRM under part 5, the term hazard has a specific, formal meaning rooted in Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) definitions.

FAA definition (14 CFR 5.3): A condition or object that could foreseeably cause or contribute to an incident or aircraft accident, as defined in 49 CFR § 830.2.

ICAO Definition (Doc 9859, 4th Edition): A condition or an object with the potential to cause or contribute to an aircraft accident or incident.

In practical terms for SRM, a hazard is any existing condition that makes an operation, activity, or process less safe by increasing the likelihood of an incident or accident. A hazard is neither the negative event itself (that’s a consequence), nor the reason the condition exists (that’s a cause or contributing factor)—it’s simply the condition or object that introduces risk into the system.

Examples of correctly written hazards:

Visibility below published minima

Mixed‑experience flightcrews in high‑workload conditions

Initial operations at an unfamiliar airport

Frequent task interruption during critical maintenance steps

Incomplete supplier documentation for a flight‑critical part

Calibration drift in a tool used for structural inspection

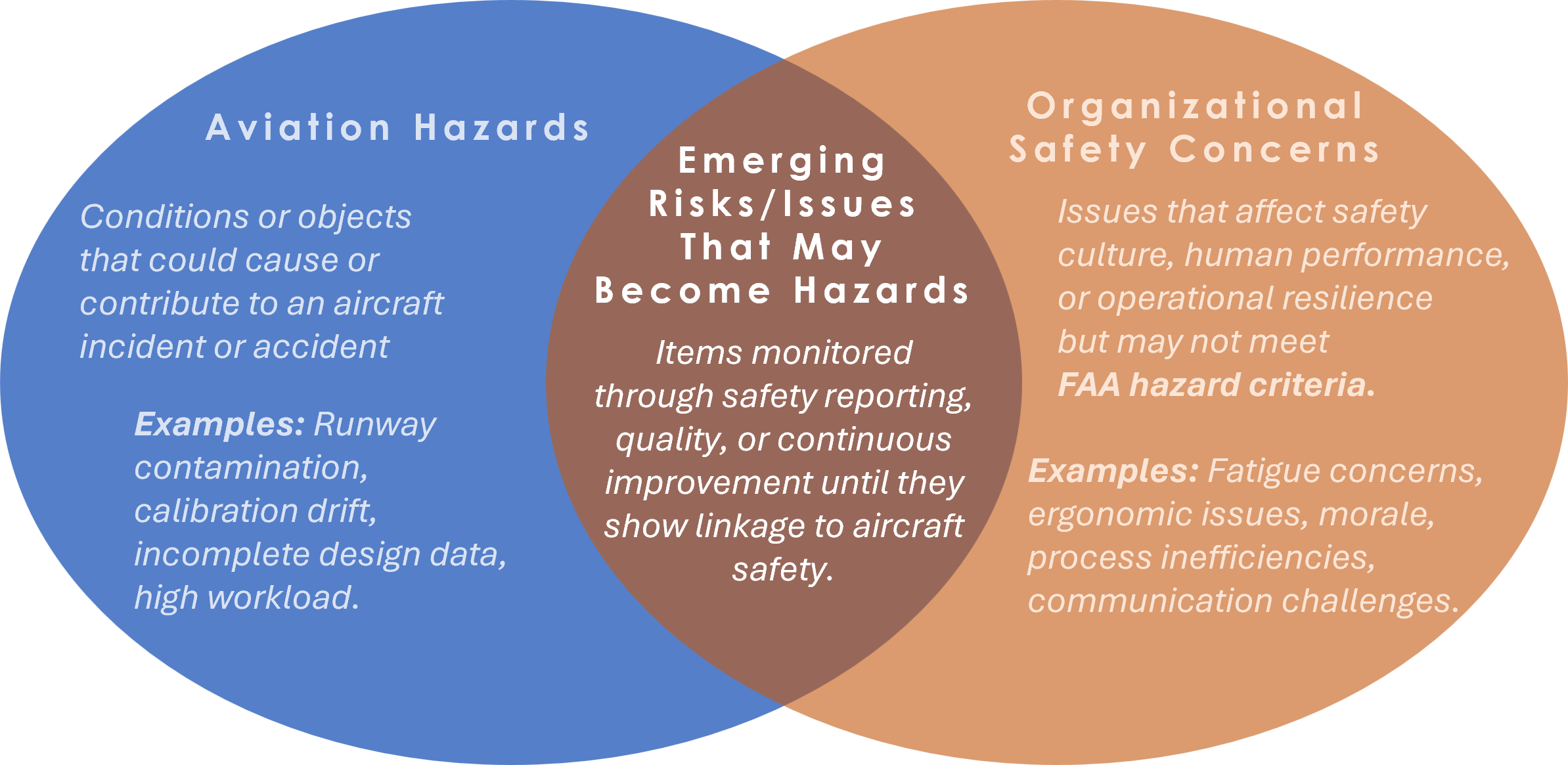

✈️ Managing Scope: Regulatory SRM vs. Holistic SMS

Although the FAA/ICAO definition governs what must be analyzed through formal SRM under part 5, Subpart C, many aviation organizations wisely choose to monitor and address a broader set of safety concerns.

Key distinction:

Regulatory SRM under part 5 applies only to hazards that could cause or contribute to an aircraft incident or accident.

A holistic SMS also addresses organizational safety concerns that might not meet that threshold.

Sticking to the official hazard definition in SRM is important because it:

Keeps the SRM process focused and manageable,

Ensures SRM outputs remain tied to aviation safety outcomes, and

Aligns your documentation with FAA intent and inspector expectations.

At the same time, many organizations often choose to track issues such as:

Human performance challenges

Fatigue concerns beyond regulatory limits

Equipment reliability issues

Near misses or interruptions in workflow

Workplace conditions that may not yet rise to an aircraft‑safety hazard

Communication or culture issues

These may not meet the FAA definition today, but may be early indicators of emerging risks.

How to manage both without muddling SRM

Route broader safety issues through a parallel process (for example, safety reporting, quality management, continuous improvement).

Elevate issues to formal SRM if they begin to demonstrate a credible link to aircraft safety.

Encourage employees to report broadly—let the SMS decide which concerns require SRM.

This preserves regulatory clarity while promoting a proactive safety culture.

✈️ Why Hazard Identification Is Challenging

Most organizations can describe what went wrong after an event, but describing hazards before something happens is more difficult. FAA SRM job aids and workshops, along with other SMS training material, frequently note teams tend to:

1️⃣ Confuse outcomes with hazards.

“Runway excursion” is not a hazard.

“Runway contaminated with standing water” is.

2️⃣ Confuse causes with hazards.

“Poor training” is not a hazard.

“Training program does not include abnormal procedures for X system” is.

3️⃣ Jump to solutions too early.

Teams frequently start proposing mitigations before the hazard is even defined.

4️⃣ Not linking hazards to the system and environment.

Hazards emerge where your systems and their operating environments meet.

✈️ Principles of Effective Hazard Identification

1️⃣ Hazards arise from system‑environment interactions. This is consistent with guidance from Advisory Circular (AC) 120–92D, Safety Management Systems for Aviation Service Providers, that a thorough system description is the foundation of hazard identification. When you understand your systems, you know what must go right. When you understand the environment, you know what might go wrong. Hazards emerge where your systems and their operating environments meet.

2️⃣ A hazard is a condition—not a failure, not a consequence, not a fix.

Correct: “High crosswind component on a short, contaminated runway.”

Incorrect: “Pilot error.”

3️⃣ Hazard identification should be structured, not ad hoc.

Consistency matters. The FAA encourages organizations to use a repeatable method tied to the system description.

4️⃣ Use FAA‑aligned taxonomies to strengthen consistency.

Using hazard classification taxonomies from the Safety Management International Collaboration Group (SM ICG), the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST)/ICAO Taxonomy Team (CICTT), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) helps classify hazards by:

Environmental: Conditions such as weather, wildlife, or other external factors affecting operations.

Technical: The system’s aerodrome, air navigation, aircraft, maintenance, or design/manufacturing aspects.

Organizational: Management structures, policies, documentation, and operational processes or procedures

Human: Human performance and limitations that can affect how people interact with the system.

These taxonomies support trend analysis and improve SRM documentation.

✈️ A Practical 3‑step Method for Hazard Identification

Step 1: Start with the System & Environment Description

Use your system and operating environment analysis (described in Part 1 of this series) to meet 14 CFR 5.53’s requirement to describe the system in context and to anchor your hazard identification in real operations.

Step 2: Ask “What Could Reduce the Margin of Safety?”

Prompts that help:

What assumptions must remain true?

What conditions create variability or uncertainty?

What external factors influence performance?

Where do people interact with complex steps or interfaces?

Step 3: Write Hazards as Clear, Objective Conditions

Examples:

“Environmental contamination affecting calibration.”

“Inconsistent supplier documentation for flight‑critical part.”

“Fatigue during extended duty periods.”

“High workload during critical phase of operation.”

✈️ Examples of Hazards (General Across Sectors)

Operational environments

Runway contamination

Complex taxi route in low visibility

High crosswinds

High flightcrew workload

Incorrect or incomplete flight‑planning inputs

Delayed distribution of revised procedures

Engineering & production environments

Variability in material properties

Calibration drift

Environmental conditions affecting equipment

Incomplete or inconsistent supplier data

Unverified assumptions in design analyses

These examples show the types of conditions SRM is designed to analyze.

✈️ Conclusion: Hazard Identification is the Bridge to Risk Assessment

Hazard identification transforms the system description into a clear understanding of what could go wrong. Once hazards are named clearly and consistently, the next SRM step—risk assessment—becomes far easier and more reliable.

Coming next in this series:

How to Assess Safety Risk (Likelihood, Severity, and Risk Matrices)

Your SMS should monitor both circles—but only the left circle (aviation hazards under the FAA/ICAO definition) requires formal SRM under 14 CFR part 5.

Do you have questions or concerns about SMS? Share them with us!

PAI Consulting | Helping you succeed. Learn more.

Any opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not the opinion of PAI Consulting. In addition, this article may contain links to third-party websites. PAI Consulting does not endorse or make any representations about them, or any information, software, or other products or materials found there, or any results that may be obtained from using them.

We welcome thoughtful and respectful discussion.

To keep this space safe and productive, please follow these guidelines:

Be respectful. Personal attacks, name-calling, and abusive language will not be tolerated.

Stay on topic. Keep comments relevant to the content of the post.

No spam or self-promotion. Links and promotions that are not relevant to the discussion will be removed.

Use appropriate language. This is a professional environment—please avoid profanity or offensive language.

Protect privacy. Don’t share personal information—yours or anyone else’s.

You may reply to, like, or flag other comments.

Comments are moderated and may be edited or removed at our discretion.

By commenting, you agree to abide by this policy.