Understanding Systems & Operating Environments in Safety Risk Management

The First Step in SRM Under Title 14, Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) Part 5

When organizations begin implementing Safety Risk Management (SRM), one requirement often feels daunting: describing the system being analyzed and the operating environments in which it functions. It’s the first step in SRM under 14 CFR part 5, yet it’s one that many operators, engineers, and manufacturers find challenging.

Whether your organization operates aircraft, maintains them, or designs and manufacturers aviation products, SRM always starts with the same question: what system are we evaluating, and under which conditions does it operate?

This post breaks down these concepts and prepares you for the next step: hazard identification.

✈️Why This Step Matters

SRM is not a free‑flowing brainstorming exercise—it is a structured, context‑driven process. Part 5 requires system and environmental descriptions because the risks associated with any activity depend on how the activity works in your organization.

Advisory Circular (AC) 120–92D, Safety Management Systems for Aviation Service Providers, states it plainly:

“The SRM component provides a decision-making process for identifying hazards and mitigating risk based on a thorough understanding of the organizations systems and their operating environment.”

With that foundation in place, hazards become far easier to recognize and anticipate.

✈️ What Are “Systems”

A system is any organized set of activities, people, processes, equipment, tools, software, and procedures working together to accomplish a function. (Think of a “system” as the way your organization gets something done—like how you fly a trip, fix an aircraft, design a part, or build a component.)

General examples of systems for aircraft operators:

General examples of systems for design and production certificate holders:

Part 5 does not require an exhaustive inventory of every system, only a clear description of the system you are evaluating so the SRM analysis is meaningful and credible.

✈️What Are “Subsystems”?

Subsystems are the smaller pieces within a larger system, often where vulnerabilities appear first. (Think of subsystems as the smaller steps or functions that make up a larger process.)

Broad and cross‑sector examples include—

Understanding subsystems helps you identify where risks may “hide” inside a process and where hazards might emerge long before they affect the larger system.

✈️ What Are “Operating Environments”?

The operating environment includes the internal and external conditions influencing how a system performs.

Examples relevant to operators include—

Examples for design and production certificate holders:

Environments often change faster than systems themselves (for example, new routes suppliers, and aircraft programs; test campaigns, staffing changes, or unexpected operational procedures).

✈️ Where Hazards Tend to Emerge

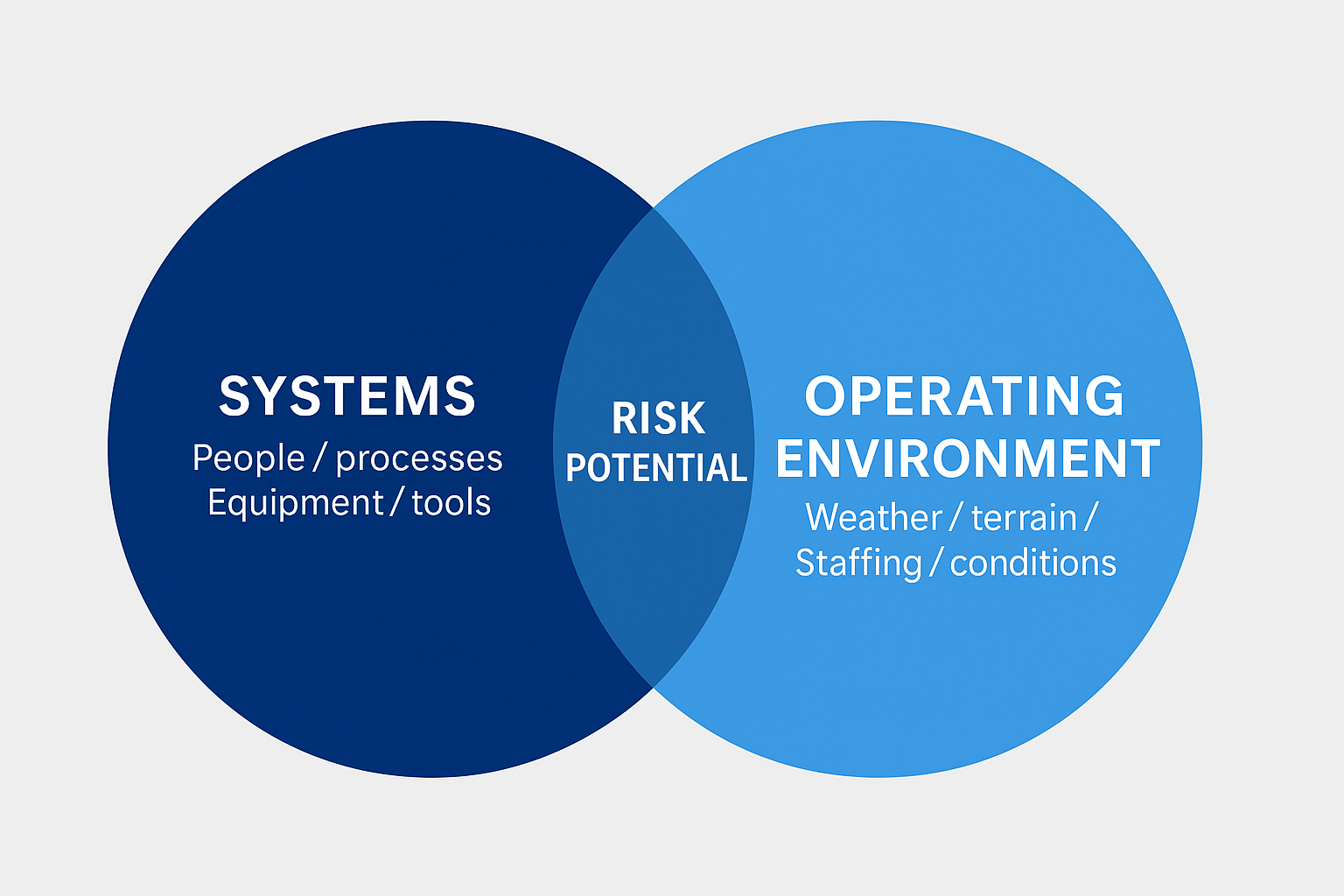

Hazards often appear not from the system alone, but from the interaction between the system and its environment.

Examples, framed broadly, may include—

Seeing these interactions is the key to effective SRM and sets the stage for hazard identification.

✈️Using Common Taxonomies for Consistency

Once you have clearly defined your systems and environment, SRM’s next step is hazard identification. To ensure your hazard descriptions are consistent, traceable, and useful for analysis (both internally and when sharing data with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or others), many organizations adopt industry‑standard taxonomies. These frameworks provide a common vocabulary for classifying the systems, environments, and factors contributing to safety events. This makes your current documentation useful for the risk analysis that follows.

FAA‑aligned and commonly used taxonomies include—

✔Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST)/International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Common Taxonomy (CICTT)

Used throughout the FAA Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) system, Flight Operational Quality Assurance (FOQA), Aviation Safety Action Programs (ASAP), and numerous FAA data programs. Ideal for classifying operational context, phases of activity, technical elements, and contributing factors.

✔National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) Taxonomy

Widely used for voluntary reporting. Especially useful for human factors, contextual elements, communication issues, and environmental conditions.

Bottom Line

Using a common vocabulary improves SRM documentation and makes hazard identification more consistent and reliable.

✈️A Simple Method for Describing a System and Its Environment

Before starting hazard identification, walk through these quick steps:

- Identify the system you’re evaluating (function, purpose, scope).

- List the key subsystems or major components.

- Describe the environment (conditions, constraints, interfaces).

- Note what changes or pressures could influence the system.

- Confirm who interacts with the system and how.

This simple method satisfies part 5’s requirement for system analysis and creates the structure needed for the next SRM step.

✈️ Setting Up the Next Step: Hazard Identification

Once you understand the system and its environment, you’re ready to begin identifying hazards—the next post in this SRM series.

With your system and environment defined, you’re now ready to identify hazards in a way that lets you—

- Recognize conditions that could lead to undesired outcomes,

- Use FAA‑preferred taxonomies to classify them, and

- Prepare for risk assessment and risk control selection.

Coming next in the series: How to Identify Hazards Effectively (for Operators, Designers, and Manufacturers).

Check out other articles on our SMS Quick Takes page.

Do you have questions or concerns about SMS? Share them with us!

PAI Consulting | Helping you succeed. Learn more.

Any opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and not the opinion of PAI Consulting. In addition, this article may contain links to third-party websites. PAI Consulting does not endorse or make any representations about them, or any information, software, or other products or materials found there, or any results that may be obtained from using them.

We welcome thoughtful and respectful discussion.

To keep this space safe and productive, please follow these guidelines:

Be respectful. Personal attacks, name-calling, and abusive language will not be tolerated.

Stay on topic. Keep comments relevant to the content of the post.

No spam or self-promotion. Links and promotions that are not relevant to the discussion will be removed.

Use appropriate language. This is a professional environment—please avoid profanity or offensive language.

Protect privacy. Don’t share personal information—yours or anyone else’s.

You may reply to, like, or flag other comments.

Comments are moderated and may be edited or removed at our discretion.

By commenting, you agree to abide by this policy.